An Interview with Kenichiro Inoue

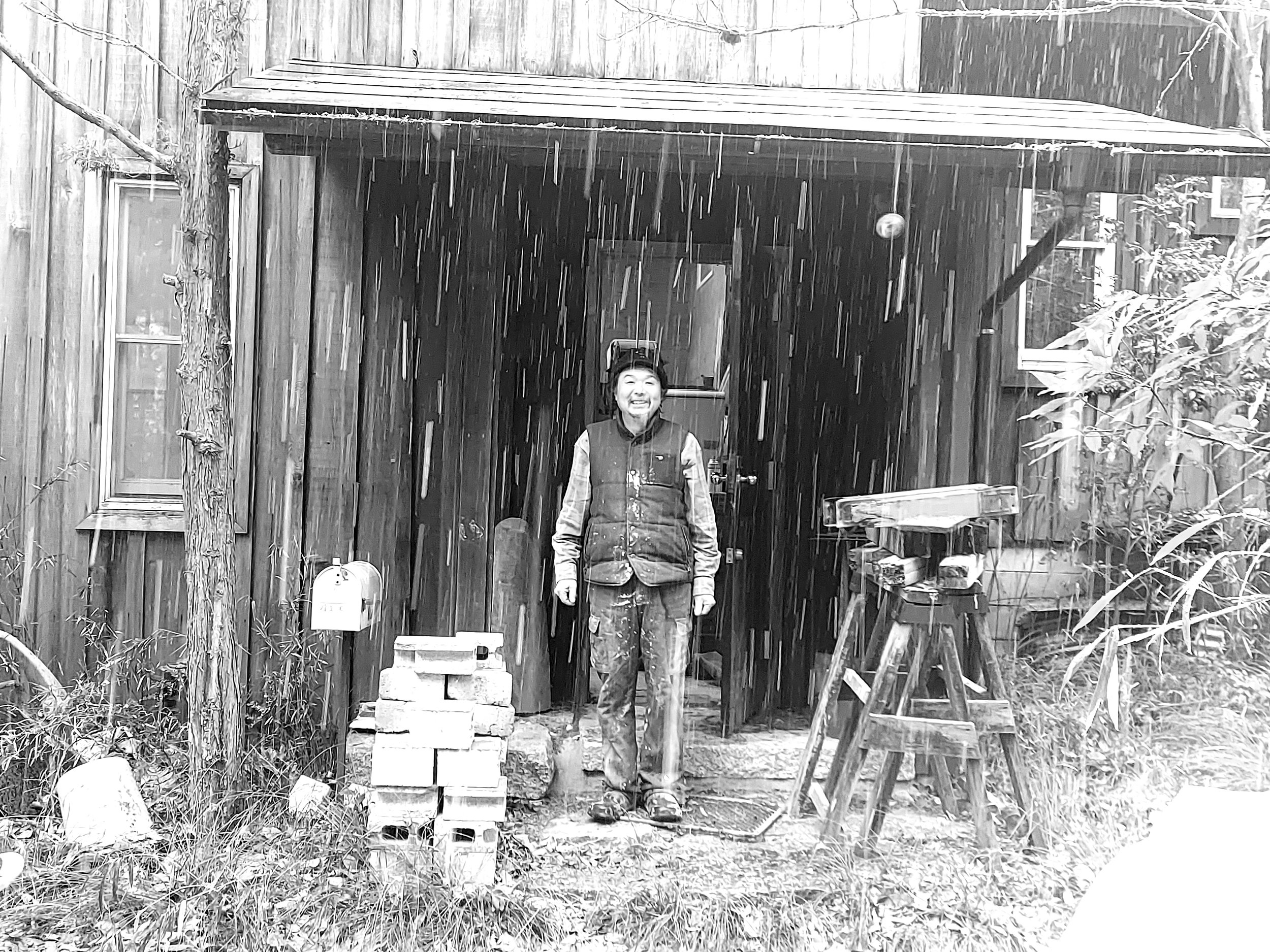

We visited Kenichiro Inoue at his studio in Kasama, to discuss his life and career in ceramics.

When Kenichiro Inoue saw the packed train going in one direction, he realised he had to go in another. It was towards the end of the 1970s and born into a salaried household in Tokyo, the natural course of events would have been for Inoue to aspire to board the Shinjuku commuter train. But he resolved to return the ticket.

Instead, Inoue embarked on a journey to the hills north of the capital and the ceramic town of Kasama. His path tells the story both of the creation of his identity in pottery; and the wider situation of Japanese society and ceramic art in this period. The outcome is an expressive collection of work that could only really be made in Japanese ceramics, in Kasama.

Japan’s high growth period took off in earnest in the mid-1960s, continued through several oil shocks in the 1970s, and became frothy asset bubble in the 1980s. The competition to get a foothold, and a piece of the action, was at times intense. For Kenichiro Inoue, a keen surfer who had misfired in university entrance exams, the tide of suited office workers at the station was alienating to behold. “I just knew that I wanted to do something different,” he said, speaking at his Kasama studio.

A pamphlet he came across at his vocational school gave him a hint of what he could do. It included an account from one of the early students at the Kasama ceramic training school (the present university), that resonated with other experiences in Inoue’s life. On his surfing trips to the ocean east of Tokyo, the coastal towns were not yet developed as resorts. Instead, Inoue lit campfires at the unspoilt tree line, and gained a taste for life outside the metropolis.

“In the pamphlet, the student said he earned money from making ceramics. I thought, ok, there is this kind of work in the countryside”

Having resolved to leave for the creative hinterland, Inoue pieced together training from vocational school, Kasama’s college, a ceramic works and the potter Shigeo Sudo. His surroundings became their own teacher, with a crop of aspiring young ceramicists, and Inoue’s developing interest in contemporary art. “I think the atmosphere of Kasama suited me. In other ceramic areas, there is a set style and they tell you what to make. But in Kasama, it was whatever worked. For an area of traditional crafts, it was incredibly free.”

Moving to establish his own studio in the early 1980s, Inoue developed a style untrammelled by convention. This ultimately settled on two areas of work: one characterised by expansive hand-painted flowers. Camellia and chrysanthemums. And another of pop-art influenced illustrations on traditional Japanese forms.

Before Inoue’s brush could fully speak he needed to earn a living, and here Japan’s consumption economy provided an assistance. In his retelling, for a period Japanese handmade ceramics had become expensive items purchased on the top floor of department stores. But coinciding with his arrival in Kasama, a market emerged for pieces by individual ceramicists sold in new independent stores around the capital. There was a steady flow of buyers to Kasama, and no shortage of demand. “In any case everyone was young, and they were interested in what we were making. And it was cheap! We didn’t really know what we were doing and there was hardly any margin, but in that economy we received many orders, and they said we will buy however many you can make.”

The burgeoning indie scene of the period crossed to the mass market, and this created an easy safety net to experimentation. This failed, however, with the collapse of the consumption economy at the end of the eighties. “The buyers who used to come for 100-200 reasonably priced works, expensive ones too, now occasionally called and said ‘errr… could I have three of those. Or maybe one of those,’” Inoue recalled.

A new era now began, symbolised by Kasama’s annual Himatsuri pottery festival, of ceramic artists working directly with their customers. As in numerous episodes in the town’s history, the situation stabilised with the potters at the lead. For Inoue, the more craft-orientated 1990s gave him a chance to develop the quality of his work. The camellia flowers became stronger, bolder and ever more skilfully painted. His gallery habit also showed him another direction.

Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat… were perhaps not typical reference points for a Japanese traditional ceramicist, but for Inoue, in Kasama, there was no reason not to be inspired. The designs he drew and then engraved into glaze using the kakiotoshi technique, began to spread across the pieces. TVs, radios, fish, and more recently industrial factory scapes, inspired by the photo albums that pile in Inoue’s studio. “In traditional ceramics, for example in the Azuchi-Momoyama period, they depicted the culture of time. Such as waterwheels, or ox-drawn carriages in the patterns of kimono. I just started to think what we would depict if we depicted today.”

These are still Japanese ceramics in form, including katakuchi sake pourers and small soba choko cups. But their surface design is all modernistic hieroglyph, with patterns that show nature, and human-made objects. Most frequently in the monochrome palette he developed in the 1990s, Inoue occasionally throws back to the bright gold lines popular in the early period of his work.

Inoue did not choose a career in ceramics for its stability, rather he entered Kasama as a point of refuge from the Tokyo rat race. He experimented, planted roots and found a place to be himself. He marvels today at the seriousness with which the present generation of students at the ceramic university approach their assignments - while recognising that his was a different era. It was one where craftspeople could develop their skill to deliver ceramic art for everyday life. This accorded with Kasama’s roots as a place where farmers converted to ceramicists, for economic reasons, but also to express the aesthetics of their community Inoue now speaks with a sense of satisfaction, as someone who avoided a tide of conformity, and rode a wave. A peace and a creativity, that continues to build in him today.